| |

Reimon Bachika

International Website of GHA "Peace from Harmony" Board Member

The GHA Honorary Member

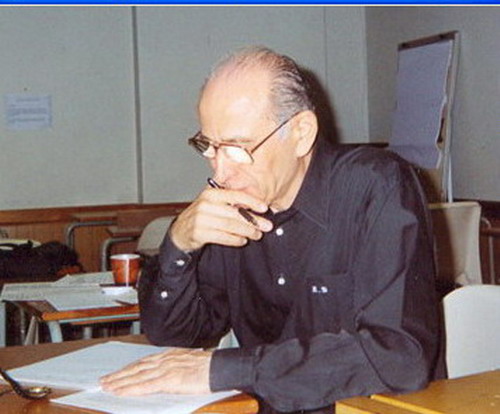

With the students: 2007/03/14

Professor of the sociology of religion at Bukkyo University, Kyoto, Japan

See also: Tetrasociology and Values: http://www.peacefromharmony.org/?cat=en_c&key=154 (and below)

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

SPHERONS: GENOME of GLOBAL PEACE and GLOBAL HARMONY. Review of Argumentation: http://peacefromharmony.org/?cat=en_c&key=747 Reimon Bachika

Introduction

Global Peace Science (GPS) is a logical enlargement of Dr. L. Semashko’s Tetra-sociology. It can be seen as the crown on his four-dimensional social philosophy. (Cf.: http://peacefromharmony.org). The author reformulates basic tenets of K. Marx’s social classes and the dimensions of sociologist Talcott Parsons’ theory about the functional prerequisites of socio-cultural systems. Semashko’s theory classifies people based on their social involvement in 4 spheres of social production that are constant: (1) as a total population/people (the socio-sphere), (2) people engaged in the sector of information (the info-sphere), (3) the organizationally engaged population (the org-sphere), and (4) technologically engaged population: the techno-sphere. In turn, the GPS theory classifies the complexity of social realities and human relations in a total of sixteen subdivisions of the original four spheres. one important point is that the functioning of social spheres and societies as a whole has to be understood as ‘autopoiesis’, or self-production (cf. sociologist N. Luhmann and biologist H. Maturana). The author claims that in this way his social philosophy captures the essence of individual action and societal functioning. Another crucial point is that some past and present societies, or “parts” of them, are totally disharmonious and on the wrong track—dominant empires, groupings of the aggressive countries, outcasts, fascists, terrorists, and criminals are the main examples. This is why the author calls his social philosophy a theory of “spherons” and “partons.” (These are new terms that are formed in the same way as the words electron, neutron, etc. in nuclear physics. Leo confided to me that, in case they sound unusual, they could be replaced by more adequate idioms). Ultimately the logical premises of the Spherions’ theory are totally satisfactory. Appreciation and critical remarks. Firstly, the ultimate goal of Dr. Semashko’s social philosophy is very lofty. What can be better than laboring for eliminating the horrors of war and achieving world peace? For many, it is literally a matter life and death. This theory is also sociologically sound. The most important issue concerns the structuration of societies. It is societies as collectivities that determine basic national policies and their outcome for people in their everyday lives. Secondly, many other earnest people would agree with Semashko’s noble thought, but may have doubts e.g., about his core concept of social harmony. Its content might be improved. The ultimate goal of harmony among people is a matter of what is good for all people. In other words, it is a matter of values. Yet, values represent knotty attitudes. Consider the scope of idealistic values: sincerity, friendship, fraternity, equality, the beautiful, the truthful, liberty, faith—religious and profane.…Other values embody material benefits: wealth, fame, and power over fellow humans. It is hard to find a common characteristic in their variability, except that all values incorporate affect and feeling that tend to counteract rationality. Yet, the term harmony indeed could be chosen to express the structural essence of societies and nations. The ultimate goal of world peace is unthinkable without peace within each national society. Harmony can be seen to represent the most important social value. All the same, I’d like to argue that our author’s Global Peace Science and its idea of harmony resembles mental DNA or a genome. This is a metaphor expressing the complexity of the human psyche and the diversity of the networks and institutions that people invent. Metaphorical explanation is not yet science in a strict sense, but it could become much more so in the future, if many more scholars, educators, politicians etc., get on board of the global peace plane. References/Bibliographic note 1.Semashko, L. (2016) Head Editor & 173 coauthors from 34 countries. Global Peace Science: The Common Good, Human Rights, Revolution of Social Sciences for Creating Peace, Harmony and Liberation from War (title newly edited): a World Textbook, first edition in English, Smaran Publication, New Delhi, 616 pages, ISBN 978-81-929087-8-6 http://peacefromharmony.org/docs/global-peace-science-2016.pdf 2.Semashko, L. (2002) Tetrasociology: Responses to Challenges. St.-Petersburg State Polytechnic University, ISBN 5-7422-0263-4: http://peacefromharmony.org/docs/2-1_eng.pdf 3.Bachika, R. (2003) “Tetrasociology and values”, in: Tetrasociology: From a Sociological Imagination Through Dialogue to Universal Values and Harmony.ISBN 5-7422-0445-X: http://peacefromharmony.org/docs/2-2_eng.pdf 4. Bachika, R. (2016) Individual and Collective Misfortune: Possibilities of Transcendence: http://peacefromharmony.org/?cat=en_c&key=701 Reimon Bachika is Professor Emeritus, Dept. of Sociology, Bukkyo University, Kyoto, Japan. Personal page: http://peacefromharmony.org/?cat=en_c&key=24 May 1, 2017 Published: http://peacefromharmony.org/?cat=en_c&key=747 -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Dear Reimon, The GHA members are very happy that Global Peace Science (GPS) books were arrived in Japan, to you as the oldest GHA member, one of its founders and one of Tetrasociology/GPS coauthor since 2002! Japan is the eighteenth country in a row, including India and Russia, which received the GPS book copies from GHA: Argentine, Armenia, Austria, Bulgaria, Brazil, Ghana, Greece, Iran, Kazakhstan, Malaysia, Nigeria, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, USA. + Many Governments, Universities, Libraries, International Organizations, including UN, UNESCO etc. are. We hope that one copy will be send to your wonderful peaceful PM, who established the friendly relations with Russia and its President Mr. Vladimir Putin. Putin have long received this book as the USA President Mr. Donald Trump from Dr. Rudolf Siebert. They three are very needed in this science to build global peace together and exclude any war, especially nuclear.

Many thanks for your warm words about GHA.

Cordially, Best wishes for peace from harmony of SPHERONS,

Leo

01-04-17

Dear Leo,The good news: the books arrived today! They are a great sign of your "qualifications of personality, motivation, professional academic work, sense of purpose and leadership.” Soon, they will be on their way to 3 colleagues.

Congratulations again.

Reimon Reimon Bachika,

Professor Emeritus, Sociology, Kyoto University, Japan, Kobe,

Personal page: http://peacefromharmony.org/?cat=en_c&key=24 01-04-17

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Individual and Collective Misfortune: Possibilities of TranscendenceHuman Dignity and Humiliation StudiesReimon Bachika, Kyoto, Japan2016 ABSTRACT How did people overcome the massive misfortune of World War II? This essay primarily focuses on the experiences and later thought of Rudolf J. Siebert, a German author, who as an adolescent conscript and survivor of that war, turned into a prolific scholar and developed a moral high ground leading to a religious transcendence of the utter meaninglessness of large-scale evil. This author’s lifework seems to have shaped an alternative identity as a person deeply committed to a different humanity and a revitalized religious faith, which appears to embody a model of spiritual transcendence. Others, M. Gandhi and N. Mandela for instance, much suffering not withstanding, attempted to affect a cultural and/or a social version of the same in their countries. Sociologically, the paper discusses the implications of personal and social efforts for overcoming misfortune. In particular, it reasons about the primacy of the collective dimension of being human, yet, at the same time, it argues that the overcoming of doubt, anguish, and grief should be easier when disparity between personal and a collectively held frame of belief is slight, that is, when one can depend on broad collective resources.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

On the Sociological Congress in Durban, July 2006

Professor of the sociology of religion at Bukkyo University, Kyoto, Japan

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Bio

Reimon Bachika is professor of the sociology of religion at Bukkyo University, Kyoto. He served as President of the Research Committee of Futures Studies (RC07) of the International Sociological Association during 1997~2006. Bachika was born in Belgium in 1936, did religious studies in Louvain, Belgium (1958-62), and completed graduate studies in sociology at the University of Osaka, Japan (1966-75). He is co-author of An Introduction into the Sociology of Religion, (in Japanese, with M. Tsushima, 1996), editor and contributor to Traditional Cultureand Religion in a New Era (Transaction 2002), contributed to several other books, and wrote numerous articles both in Japanese and English on the sociology of religion and related problems of culture and values. Presently he is working on a book on Symbolism and Values. Reimon BachikaProfessor, Dept of SociologyBukkyo University

Address:Bukkyo University96, Kitahananobo-cho, MurasakinoKita-ku, Kyoto603-8301, JAPAN

Tel. (075)491.2141fax. (075)493.9032January 31, 2007------------------------------------

Hiroshima, No More

Hello People of Planet Earth Look West, look East See Nippon’s Constitution for Peace No more war No more army. In just one day Thousands of children died Thousands of mothers died Thousands of boys and girls died Thousands of men and women died and elderly: Thousands and thousands and thousands All in one day In one city. Yet, another city had to follow Flattened, burnt, scorched In a moment of infernal rage. Says Nippon’s Constitution for Peace: No more war No more army. Oh People of Planet Earth That we need A constitution for peace In every person’s heart.

June 18, 2009. Reimon Bachika, Professor Emeritus, Bukkyo University, Department of Sociology, Kyoto Japan The USA won the final phase of WW II with Satan on its side. Other powerful nations engaged the same Devil and keep him in their backyards. More power-hungry nations long for the same ally of Hades. Can this demonic urge be stopped? I do not know, but it should. We can look back, once again, at what happed in Hiroshima and Nagasaki 64 years ago. We can find inspiration in Japan’s Peace Constitution that represents the saner and greater part of Nature, Life, Peace, and Harmony loving Japanese. May many nations follow Japan’s decision to make war unconstitutional.

----------------------------------------

A report from Seoul: Since many of GHA were interested in joining this first meeting of the World Civic Forum Conference (Seoul, May 5-8, 2009), sponsored by Kyung Hee University* and UN's Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UNDESA), I would like to write a few lines to report about it. Recent sociological conferences have begun to discuss “public sociology,” meaning that sociology should be directly involved with social actors, that is real people. This conference was very good in this sense, perhaps a model of "public social science" in that it involved diplomats from the UN, presidents of UNOs, government officials, University directors and, of course, many academics. I especially received strong、favorable impressions from the speeches by Sha Zukang, the Chinese Under-Secretary of the UN, Paul Kennedy* and particularly from pale anthropologist Donald Johanson, who discovered the skeleton of Lucy, an anthropoid primate of 6 million years ago. The conference was titled as in the heading and logo above. It's sub-themes and thematic sessions were as follows--the Declaration read at the Closing Ceremony affirmed the importance of these three themes: Civic Values for Global Justice; Civic Engagement in Public and Global Governance; and Civic Action for Global Agenda including Climate Change. There were about 320 presenters and around 1500 attendants. Many sessions concerned the UN's Millennium Development Goals and also Human Rights. Dr. Martha Ross Dewitt and I my self had our session the last day. Dr. Julian Korab-Karpowicz was our chair, a visiting Professor at Kyung Hee. He is a former Polish diplomat who was involved in the Solidarity Movement in Poland. By means of a colorful power-point presentation he showed many images of the rebirth of his country propelled by this movement and argued that “solidarity” could become a central value in creating a new vision for a world society. Martha elegantly presented a twelve-step progression of interactive interrelationships that determine consciousness formation, focusing on politico-economic consciousness that is reviewed and revised as socio-cultural consciousness after it is acted upon. At extreme ends of the economic continuum, the wealthiest as well as the poorest citizens are motivated by political and economic realities that may be unaltered by socio-cultural factors. Super-rich and poverty-stricken often have this in common. In contrast, my presentation concerned primarily the relevance of values. I argued that societal values and humanitarian values are important for the future of societies. Liberty, equality, and justice are societal values that have played a major role in the development of democratic societies. Harmony and solidarity may play a greater role in the future. Policy makers particularly should work harder towards the institutionalizing of these values. As for the basic, traditional, humanitarian values: the good, the true, the beautiful, and the holy, these are a matter of individual and collective autonomy. Diversity of humanitarian values must guarantee the diversity of culture. It is only societal values that should be promoted as universal values, or, as mentioned above, institutionalized as principles of social organization. Notes: * Kyung Hee University, founded in 1949, is an elite institution with 20,205 undergraduates and 3,103 graduate students. It places special emphasis on the ideals of the United Nations. Its emblem is modeled on that of the UN and its Center for International Exchanges (with foreign staff) is part of its pride. It organizes many international conferences. * Paul Kennedy, PhD of the University of Oxford, is Director of International Security Studies (Yale University). He is best known for his work The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers (1988). He has many honorary degrees and was made Commander of the Order of the British Empire (C.B.E.) in 2000 and elected a Fellow of the British Academy in 2003. Reimon Bachika Professor Emeritus Dept. of Sociology Bukkyo University Kyoto, Japan May 29, 2009 --------------------------------------------------------------

May 29, 2009Dear Reimon, Many thanks for your short but deep and impressing report. Really many in the GHA have been interested in the Seoul Conference because the theme of “Social Harmony” has been included in its agenda. However, as Martha informed, this theme has been excluded from the agenda, unfortunately. But it does not belittle a value of Conference. Unfortunately, it logo also remains for us by unknown thing. As is known, two directions struggle among themselves for a long time in sociology: ‘pure sociology’ and ‘practical (or public) sociology’. I always was the supporter of practically directed sociology, therefore I like to see, that at Conference the question “public sociology” became the central question of discussion. It promises to lift and approach the sociologists to sharp social problems of modernity, having torn off them from narrow (in all senses) empirical studies about which Pitirim Sorokin wrote, that the thousands similar studies will not replace one theoretical research focused on a social reality. A question of the civil values, engagement and actions was the second central theme of Conference as you write. This question is a question on the role of a modern civil society, which is practically focused always. Moreover, here indirectly admits, that the role of a civil society becomes priority in relation to the state and governmental influence, which often show the inability in the face of global problems. The civil society uniting NGOs is more adequate and productive in the face of these problems. one of examples of it is the GHA and its 15 projects focused on the solution of global problems through harmonization. The values theme, which you investigate many years, was the third central theme for you. You brought the big contribution to the scientific theory of values or to value sociology. This theme is constantly discussed and in the GHA and personally between us. In 2002, in connection with the publication of my book: “Tetrasociology: Responses to Challenges” (St-Petersburg, 2002, 158p.: http://www.peacefromharmony.org/? cat=en_c&key=145) you written remarkable article “Tetrasociology and Values”, which has been published in the collective book of 15 co-authors from 6 countries: “Tetrasociology: from Sociological Imagination through Dialogue to Universal Values and Harmony” ( St-Petersburg, 2003, 394p, in three languages: Russian, English and Esperanto: http://www.peacefromharmony.org/? cat=en_c&key=149). Your article has kept actuality until now; therefore I send it (6 pages) for all co-authors of the GHA antinukes project, in which value of harmony takes a key place. I completely share your deep ideas about institutionalization of harmony in social organisation. In the GHA Magna Carta of Harmony (2007: http://www.peacefromharmony.org/?cat=en_c&key=3) we consider institutionalization of harmony in social structure of the sphere classes of population, in the state, political system, democracy, harmonious education, management, reserve currency and etc. In our antinuclear project harmony finds a new direction of institutionalization through “International Treaty on Global Harmony” as the guarantor of collective safety and nuclear disarmament. I also completely share your deep idea about diversity of values as the guarantor of diversity of cultures, each of which is based on own value accents, that distinguishes them and only value of harmony connects them, keeping their diversity. Obviously, a value of solidarity possess similar uniting mission also, which accented, as you write, Polish colleague-sociologist and diplomat from "Solidarity". Your statement: “Policy makers particularly should work harder towards the institutionalizing of these values” is especially actual in the channel of the GHA antinukes project realization as nuclear disarmament is impossible without global harmony and solidarity on this basis, i.e. solidarity in harmony and for harmony. In this connection, we could invite in the project Dr. Julian Korab-Karpowicz as one of its co-author and expert. Could you invite this Polish sociologist on GHA behalf? Once again many thanks for your report which inspires and enrich us and generate new theoretical and practical ideas. I will be happy to publish your report and possible responses to it on your page of our site ‘Peace from Harmony’: http://www.peacefromharmony.org/? cat=en_c&key=24. Best harmony wishes, Leo Dr. Leo Semashko GHA President --------------------------------------------------

Towards Harmony in the Religious Sphere: Focusing on Symbolizations and Values Religion: peace and conflict (1) Seen inter-religiously, the present world still witnesses many instances of conflict where religious sentiments seem to be at odds. Tensions are not limited to widely differing religious traditions such as Christianity and Islam, Islam and Hinduism, Judaism and Islam -- in some conflict situations deep-running ethnic fault lines appear to be the greater problem. As is the case of the Christian and Buddhist Churches, tensions occur within the same tradition, though less and less frequently and to a lesser degree. Certainly, in our age, many old and new religious organizations are peaceful agencies. Many new religions profess to advocate world peace. Many individuals in religious orders, churches, organizations, and other religious groups appear to be wholeheartedly devoted to personal or social ideals, but there are notable exceptions. Some religiously oriented groups commit acts of violence and some have become notorious for their misdeeds. How to make sense of this contradictory situation in the world of religion? Could it be, as is suggested by some researchers, that the ‘religious factor’ somewhere contains a defective gene as it were, or, is it more plausible that particular individual leaders bear greater responsibility for religious strife? Two points from this introductory note are important in the present context. First and most important for this paper, since religiously aggravated conflict is not rare in our age that reached a high degree of civilization, it must be that the reasons why it occurs are still are not yet well known. Secondly, one may not forget that the world of religion is very diverse in terms of beliefs and practices that are not easily brought into harmony with one another. Also, social situations are never quite simple and many bones of contention are fought over in particular situations. Even if the world of religion as a whole were not substantially better than other areas of society, we have to be wary of popular or anti-religious stereotypes that see religion itself as a cause of war. The goal and scope of this paper are very limited. A full-scale explanation of religious conflict is not attempted. The paper asks attention for the socially positive and negative functionality of symbols and values as elements of culture, which in various ways are also the paramount features of religion. Its aim is to arrive at an understanding of values and symbols that can contribute toward more harmonious relations among religious groups. This possibility suggests itself given that both differences and common ground in the religious sphere are easily clarified and because the characteristics of values and symbols show how they can be used socially. In final analysis, if change for the better is possible at all, it must start in the minds of people. Let us first consider some examples of religiously muddled strife. Belfast, Jerusalem, Ayodhya Closest to home, the case of Northern Ireland remains on the list of conflicts where mutual understanding is lacking. Over the years, violence has been occasioned by the annual parade of the Protestant Orange Order in Belfast, presumably due to the ban of marching through a Roman Catholic neighborhood. A parade featuring traditional community garb and music is an enjoyable event. Essentially, there should be nothing wrong with the event as it is performed annually, but its interpretation by both parties may be misguided. The Protestant side holds this march as a commemoration of their victory in a civil war with the Catholics 300 years ago. That is, they continue to evaluate highly a commemoration of an historical event. The Catholic side seems to take offense and does not want to let this procession pass through its neighborhoods. Thus, the focus of this conflict around the parade is a particular symbolization. How important is this to those concerned?

The controversy around Jerusalem as the capital of both a Jewish and a Palestinian state is much more complex due to heavy economic and political considerations, but it has a similar dimension to it. Jerusalem is seen to have considerable symbolic meaning to both Israelis and Palestinians, who have occupied the place for several centuries and therefore feel attached to it so as to want exclusive possession. To an outsider, an administrative capital without a religious aura is easily acceptable, even perhaps dual administrative facilities for politically different nations in one and the same city. Better still, the idea of Jerusalem as a holy city of the three religions that have sacred sites in the region is a dream of harmonious and peaceful relations among those religions and a showcase for others. Are symbolic entities difficult to share?

Again, a similar situation exists in Ayodhya, India, where both Muslims and Hindus contest a much smaller holy place, the site of a mosque that was destroyed ten years ago and has been rebuilt as a Hindu temple. Originally, the site in question is said to have been sacred to Rama, a Hindu god. After being conquered by Muslims, the sacredness of the place was reversed in favor of the conquerors. Several people have been killed in recent strife. Considered rationally, a temple could be built in any place that is rightfully acquired. Has a symbolic place more value than human lives? Individual and collective identities Values appear to have greater significance for personal identity, while symbolizations have greater weight for cultural identities. As for the first, it is easily understood that work and various organizational and/or cultural achievements are central to one’s sense of self-fulfillment and self-respect. Closely related are financial gain and social prestige that usually ensue from playing central roles in an organization. on a different level, as American politicians tend to say, people involved in religion usually evaluate highly their particular religious faith and sense of morality, not only for their personal but also for their public life, even though values do not determine their behavior in every detail. To repeat, work, achievements, social status, and particular instances of faith can be seen as representing values that enhance one’s sense of personal well-being and identity. In contrast, while also personally gratifying to a certain degree, things that are held in common with others within a class, a status or an age group, are features of cultural identities. For instance, wearing an earring by a young adult or man may be a token personal pride but is also a cultural association with a sort of avant-garde in men’s fashion in modern societies but that presently appeals only to a small number of youths and adults. Certain things shared with a collectivity of people seem to be symbolic due to their group reference. It is of course well-known that religious and ethnic groups hold a number of cultural elements in common. Think of particular pieces of garb, specific head cover, turbans, veils, beards and other hair growth or its shaving in different cases. We know that many ethnic groups have their own language and that some observe proper culinary and other cultural practices. Most churches enjoy their own religious celebrations, practice their own forms of ritual, and follow their own religious customs. The older churches, Buddhist, Shinto, Roman and Orthodox Christianity stick to a traditional ritual or liturgy, using a great many symbolic objects (objects are symbolic when they refer to a reality commonly not associated with these objects). Again, the older religions have their shrines, temples, churches, and mosques built in a religiously specific architectural style. Some later founded denominations and new religions tend to have less specific religious culture or ritual. Some rely heavily on symbolism, while others do not. The latter probably derive greater meaning from other religious practices, meetings, social activities, etc.

All the referred to cultural elements, pieces of clothing, instances of ritual and specific patterns of behavior are shared by a group. They constitute distinct cultural practices and customs. People feel at home with these practices if they have been exposed to them since childhood or if they have consciously chosen to identify with them at a later stage of life. However, it is important to note that, for the people involved, what we call ritual and custom , is merely a natural part of their religious or daily life. In other words, people participating as believers in religious services and other customary practices are neither much aware of ritual, custom, nor of what is symbolic in that action. Notwithstanding, symbolism does its work without being aware of its existence. For instance, it mediates the experience of an event that is being commemorated, or the initial experiences of the founders of religions, the values they preached. It is not only as Emile Durkheim observed a long time ago that symbolism makes social life possible, symbolism plays a considerable part in fashioning the subjectivity of the participants, their cultural outlook on life. Ethnic/religious communities often are ritual communities, real communities as compared with nation-states that sometimes are said to be imagined communities. It is clear that a whole array of cultural practices and symbolic differences may produce quite distinctive cultural identities. Symbolizations, therefore, have great importance in that respect.

Seen comparatively, cultural identities are highly variable subjective phenomena that reflect many different situations in present-day multicultural societies. We cannot pursue this in any detail in this context. one important thing to note is that, in the modern age of information society, seclusion is virtually impossible and people cannot but be aware of their own and others’ ethnic/religious identity. This awareness probably is at its strongest in confrontational relationships, when taking part in ethnic/religious strife as in the above-mentioned cases of Belfast, Jerusalem, and Ayodhia. People, who in their daily lives and occupations are husbands, fathers, barbers, railroad workers, salesmen, teachers, businessmen and so on, during their manifestations and confrontations they become just marching Protestants, protesting Catholics, fighting Israelis, Palestinians, Hindus and Muslims. At that time, their identities become one-dimensional. In case of ritual/real communities, cultural identities may be much stronger than personal identities. In this case, especially when engaged in continual confrontation, it is quite conceivable that the well-being of the community is evaluated as higher in rank than the individual’s life, so that killing opponents and occasionally sacrificing one’s personal life are implicitly legitimated by the groups in question and quasi self-evident to particular persons in these groups. In severe conflict situations, identities so to speak are locked in conflict. Possibly complicated through other interests, great significance is attributed to the symbolizations of the in-group. Those of the out-group are depreciated. In other words, the symbolic elements that fashion the subjectivity of the in-group are highly treasured by that group, while those of the out-group are seen as mere markers of difference and signs of segregation. In confrontation, symbols often become objects of hatred; the foe’s flag is burnt, effigies are hanged. When a confrontation spins out of control, blood flows. The thesis I am suggesting concerning the positive and negative functionality of symbols and values is as follows. First, symbolizations, ritual, and other symbolic behaviors are very important as means of formation of a communityand a particular religious experience. Symbolizations therefore are important cultural elements and worthy of mutual respect. This is the positive side. Second, the reverse and negative side is that symbolizations can be reinforced as things of great value, resulting in 'unhealthy' invigoration of personal and collective identities. Third, values may function in unhealthy ways when they are imposed as norms, or on the contrary, when all values are professed to be totally relative in nature. Fourth, values can function properly when they are held as sources of inspiration. Thus, the problem on hand is that symbolism and valuation can be conflated. Short of overt conflict, excessively adhered to values and symbolizations are sources of dislike, distrust, and contempt. In extreme cases, they are the red cloth that excites violence. In the following sections we focus on the nature of these cultural elements and on how symbolization and valuation function in relation to each other Language and Symbolism Symbolism is a heavy-weight topic in the study of culture. The following is an interesting observation. ‘[A]single phenomenon or principle constitutes human culture and cultural capability. I have called this phenomenon “trope” for its most familiar manifestation as the perception of meaning within cultural reference points’ (Wagner 1986:126). This anthropologist discusses trope, or metaphor, as the main source from which culture springs and meaning is elicited. The word trope derives from the Greek verb ‘to turn,’ suggesting change of meaning. The same holds for the term ‘metaphor,’ and, in my view, for all symbolism that is effected through association and substitution. In other words, I see association and substitution as the core of symbolism, a mechanism through which new meaning is created or extended. This mechanism as such is simple but culture, as the totality of a myriad of symbolizations contained in language, a great part of human behavior, and the many systems of knowledge and thought, is very complex indeed. How are association and substitution basic to symbolism? Let us return to our earlier examples of cultural symbolizations. A head scarf is a piece of cloth that in Islam has acquired a particular social, religious meaning for women, and that is religiously sanctioned by this religion but not by other cultures. A little earring, worn as a kind of insignia to a modern male individual, represents an extension of meaning from an object belonging to female culture, now in part transferred to male culture. Thus our headscarf and earring show a particular association with man and womanhood. Again, in the case of the lotus flower, it is also association that transforms it into the cherished symbol of enlightenment in Buddhism through the apprehension of beauty in both cases. Other ways of association are to be noticed in the focal symbols of Christianity, Buddhism, and Islam: the cross, the wheel (of the Law), and the crescent. The Christian cross and the Buddhist war-chariot wheel in particular are powerful metaphors, because common-sense perception is left far behind and symbolic, spiritual meaning is created and represented. In all the above examples, it is neither sharing or group reference, nor a related form of action that bring about symbolism itself. It is a mind process that engenders special meaning through ‘trope’ as mentioned by Wagner: the turning around of things, activating a new perception, and eliciting new meaning that transcends common sense perception. But it is sharing that invigorates symbolism and makes it work. Generally speaking, language is a system of representation, substitution, and association and can therefore be seen as the prototype of symbolism. All words are symbolic in a broad sense. Things, actions, relationships, functions, and whatever, are represented by sounds and written characters. In most cases, there is no intrinsic relationship between those sounds/characters and the things, actions, etc., that are represented in that way. We say, language is a matter of convention, but it is more important to note that speech and language have been invented. It is very difficult to trace empirically their origin, but we can give some suggestive examples. Numerous examples can be found in Plato’s Cratylus. In these dialogues, Socrates discusses the meaning of names. Apart from what he wants to demonstrate, he observes that names, which are rightly given (when an intrinsic relationship is expressed), are the likenesses or images of the things they name. Thus, according to Socrates’ etymology, the words Uranos and Gaia (heaven and earth) derive from the Greek for ‘looking upwards’ and ‘giving birth’ respectively. The proper name Zeus derives from the verb ‘to live’ (zaoh), meaning, according to Socrates, that Zeus is the God through whom all creatures have life. The name Agamemnon, one of the Greek heroes, means ‘endurance;’ Hector, as a ‘holder of possessions,’ means ‘king,’ Orestes ‘man of the mountains,’ and so on. In this formation of names, proper nouns derive from substantive verbs or nouns. A general meaning is particularized in a person. This is both association and substitution. However, awareness of this transformation gets lost over time. Even Socrates’ contemporaries were no longer aware of this etymology.

Another interesting association is the attribution of gender to nouns in the older Indo-European languages. Why should natural, inanimate phenomena like the sun, the moon, stars, night and day, trees and mountains have gender? Those phenomena originally may have been thought of as animate things or gods even. Whatever, since there is no common-sense relationship between, e.g., night and womanhood, female gender must have been assigned to this word in Indo-European languages through association with human gender. So it goes with all the nouns in the related languages.

More common examples are the following. As we know, symbolism is effected in words that express a physical property like depth, height, broadness, narrowness, when used to express the non-physical properties of thought and meaning. Similarly, colors express symbolic meaning through association with social status in some societies and with feelings in others. In several religions, specific colors express the mood of specific celebrations as well as gradation of the hierarchy in their ranks.

To repeat, my main interest in this context concerns the fundamental characteristics of symbolism. The above examples are intended to show that symbolism comes about through association or substitution and that it causes transformation of meaning in the case of metaphors. one crucial point is that symbolism starts in the mind. Fundamentally, therefore, symbolizations are cognitive devices that, similar to the stock of words of a language, exist in great variety. As for language itself, the primary social function of symbolizations is expression and communication of meaning, not affect as Parsons maintains. The great variety in the domain of symbolization is due to the great range of thought that roams in every direction. It is also conditioned by the great variety in the physical world as the object of thought. There are numerous possibilities of creating symbolizations and new symbolic meanings.

Valuation and values In contrast to symbolizations that are primarily cognitive devices, I argue that values, while imparting also cognition, are primarily evaluation of meaning that is rooted in affect. This appears to be the case, because gratification informs valuation. That gratification is the core of valuation may appear as a paraphrasing of Parsons’ starting point of his theory:action is engaged in as gratification of need-dispositions. However, there is quite a difference. It suggests that value is inherent in action itself, as also Shils’ maintains. Adopting that proposition implies that, by acting and experimenting, people find out what is useful or effective for realizing goals and what is satisfying in terms of experience. A crucial point here is that value is inherent in an act. It is its reward. What is experienced as gratifying tends to be repeated and to become a habit. In consequence, the range of individual and collective valuation tends to narrow down to particular preferences. Very generally, the range of valuation is equivalent with the range of generically distinct actions. The assumption that gratification is the core of valuation and that value is an aspect of an act has several significant implications. It suggests, firstly, that valuation, as originating practically within action, acquires a different cognitive status as compared to symbolization that germinates in thinking. In other words, like cognition and evaluation, symbolization and valuation are distinct categories of perception. Secondly, if gratification is the core of valuation, it follows that value is not a moral concept. Anything may felt to be gratifying to an individual. Thus either being honest or dishonest, being loyal to others or deceitful, being thrifty or lazy, doing good or ill to others can be gratifying for a particular individual. Thirdly, if gratification is the core of valuation, it appears that the tone of valuation is determined not through rationality but rather through feeling. Our idea of rationality suggests continuity or accumulation. The various forms of rationality can be seen as different degrees of the same. In contrast, feelings suggests discontinuity. In other words, the various emotions appear to be of a distinct nature. This might be the reason why Max Scheler maintains that values belong to different spheres, and why others observe that our various values are not harmonious. Further, if not rationality but emotion is basic to evaluation, it seems to follow that the range of evaluation corresponds to the range of our feelings, a proposition that I hope to discuss in a follow-up. An important implication in the above is that morality and rationality are not necessarily given in individual action. This is a condition of human nature as an emergent phenomenon, which initially is a non-socialized existence and never will be totally socialized. Ways of thinking and behaving, that benefit society, tend to become recognized and legitimated by collectivities and thus become established as patterns of behavior and culture. This is another way of saying that the properties of morality and rationality are most relevant at the collective level, that they are acquired through reflection and social negotiation. The chemistry of everyday life. To everyday consciousness, symbolization and valuation are not given as distinct human faculties. Like thinking and acting, they do not function independently of each other. Notwithstanding, again like thinking and acting, these faculies are better understood as different phenomena that have distinct properties and display a divergent functioning. Analogically, one could speak of a river as an image of socio-cultural life, alluding to its fluid and ever-changing state, but the substance of a river is simply water that, in its molecular form, is rightly described as H2O, a fusion of hydrogen and oxygen gases. Since physical substances and their component elements have totally different properties, one cannot compare them with the softer blends of cultural elements. The latter do not reveal a fixed interdependency as in the case of the relations among the elemental substances in nature, but this should not mean that regularities in relationships among such core dimensions of culture are totally absent. They cannot function randomly. I argue that the mechanisms of symbolization and valuation show a definite, universal logic. Hypothetically I see them as constituting twin mechanisms, the internal human agencies that produce culture in the broadest sense of the term and that, in isolation, can be described as follows. In essence, symbolization is a mechanism for the construction, expression, and fixation or closure of meaning. Symbolizations can be characterized as 'modes of being' and 'images of behavior,' that materialize indeed as images, but also as symbolic objects, ritual, and other symbolic behavior. They are the observable, structural, core elements of culture that play a primary role in the formation of cultural identities. The core feature of symbolizations is cognition, and their main function serves communication. Due to this function, and the definite, fixed meaning they convey, symbolizations are highly useful in education as media for transmitting knowledge and improving understanding.As for their fixation of meaning, they resemble the grammatical past perfect tense of the passive voice. Symbolizations show that ‘something has been done; something has been revealed.’ People embody and live their symbolizations collectively in traditional societies (e.g., wearing veils, sporting a particular style of clothing, growing beards, and participating in ritual) and more individually in modern societies and its sub-cultures (earrings, shaven heads, fashion styles, etc.). The attraction of symbolic elements in traditional and modern settings derives mainly from sharing and from newness respectively. As cognitive devices, similar to all knowledge, symbolizations are apt to develop and multiply. The always changing items of modern fashion, goods and gadgets are obvious example, but so is the highly differentiated state of religion, which is a result of much experimenting with the production of symbolic meanings throughout the ages. Like fashionable goods, any symbolization seems as valid as any other. In other words, symbolizations seem to involve a similar logic and therefore must be functionally equivalent. In contrast, the mechanism of valuation basically is evaluation of meaning that is realized in acting. As such, valuation is a mechanism central to the formation of self and social institutions. Values, as elements of culture, are abstractions derived from individual and collective behavior. They are objectivated as ideas that become particular categories of thought. They are predominantly conceptual, core elements of culture (in contrast to symbolizations that can be seen as structural, core elements). As manifestations of evaluation, values involve hierarchy. If hierarchy is an inherent attribute of values, it cannot be said that any value is as valid as any other. The various categories of values therefore are substantially different. This seems evident when one compares actions engaged in for material/economic gain, for social/political prestige and power, or for spiritual/religious/moral benefits. However, due to substantial differences among values, one also understands that values are complementary. In plain language, many things and actions are useful, interesting, and therefore desirable. Consequently, due to the feature of priority depending on a particular situation, the hierarchy aspect or the priority of values cannot but be relative in nature. Lastly here, values have an open horizon. In grammatical language, valuation resembles the present imperfect of the progressive tense. ‘I am doing something; something is gratifying to me, and beneficial to others.’ Values then are useful to education, not for transmitting or improving established knowledge but for providing ideas and inspiring people. In aspiring to, and following up on these ideas/ideals, people work on their identities and what they can become. In this conception, one may see how symbolizations and values overlap as images/modes and ideas of behavior and being. Symbolizations resemble images (e.g., television I mages) that represent themselves as facts to which one is present. Adopting symbolizations is like wearing clothes. Newness is their great attraction in modern societies. Values in contrast are intangible and represent themselves as visions of what can be realized. People can be said to live values, too, but they do not easily incarnate values. In everyday life, people look for what is of value in various ways and in various circumstances. In the best of cases, they enjoy the simple pleasures of life, enjoy being honest, hard working, having good human relations, love nature, and so on, but all this is in the present imperfect tense. People in modern societies repeat what is useful, meaningful, gratifying in an individualized manner but nevertheless under de influence of socio-cultural climate and trends in those societies. People have different priorities at different times. one would think that the quality of life is all what matters, however for modern people variety of gratification too appears to be attractive. Such is the present chemistry of socio-cultural life. Theoretically again, both symbolizations and valuations are cognitive in nature. Both involve concepts, show a particular content, and are used for communicating meaning but, like images and ideas, they are not interchangeable. They function differently. Distinct functionality: use and misuse Different implements serve different purposes. Symbolizations and values, which are part of the same reality and are therefore much more flexible than implements and machines, have divergent properties and therefore can be used in various ways. In other words, in socio-cultural life, they can be used, for better or worse, to bolster the culture and behavior they are part of. Symbolizations (symbolic objects, social and religious ritual), as modes/images of behavior and being and as observable cultural elements show a high degree of objectivation that functions as constraint. Due to these properties, symbolizations are par excellence means of social integration (Bourdieu, 1993: 166) and possibly of manipulation. Within a particular culture, symbolizations are easily understood and accepted. However, as primarily cognitive elements, symbolizations are apt to differentiate in the same manner as knowledge. These two characteristics, a high degree of objectivation and differentiation, imply opposing tendencies. Symbolizations can be reinforced or made normative based on their constraint and their usefulness as means of communication and domination, but due to their tendency of differentiation and lack of hierarchy, imposing symbolizations appears to be against their nature, particularly so in modern, differentiated settings. Symbolizations may cause suspicion, especially to outsiders of a culture, because of their constraining force, while their tendency toward differentiation may diminish that attitude. Thus, the possibility of differentiation of symbolizations seems to counteract their constraint. Discarding them in certain cases is of no great consequence on the same account. In contrast, valuation for several reasons shows a high degree of subjectivation. For a start, value is an aspect of an act that becomes the stronger internalized the more a specific act is repeated. Specific valuations then become elements of personal identity, which, however, do not ascertain the integration of identity, because contradictory values may be internalized. Values that are internalized become elements of individual identity, are not easily discarded. However, values as ideas and conceptual elements of culture, have a low degree of constraint in contrast to symbolizations. As conceptual elements, and due to their property of hierarchy as well as their limited possibility of differentiation (they are relatively few in number), certain values are apt to be prioritized and imposed, as religious organizations tend to do. But no one value in particular should be propagated as the highest in rank, because of the property of relative hierarchy and complementary nature of values. Absolutizing specific values could create an unacceptable bias. Individual autonomy must be guaranteed. Values, due to their open horizon, serve best as human ideals and inspiration. As such, they are more durable and not easily exhausted. In turn, values may be resented because of their property of hierarchy and their substantial differences that derive from a different type of affect. If all these characteristics hold true, one understands that values too may function to fuel conflict. Towards greater sociocultural harmony Particular symbolizations are important for ethic/religious life. Culture in all its diversity, like knowledge in all its diversity, is the treasure house of the world. The sharing of a territory, a language, particular customs, religious faith, social ritual, the wearing of particular clothes and so on, are important factors for collective identity. Thus, the significance of symbolizations within a culture is beyond doubt. Regretfully, it is often overlooked that cultural differences are very meaningful overall. one can learn from different cultures, because they express differently the various meanings of life. It is in this sense that diversity may occasion respect. Without ascribing to a foreign culture, one can wonder about its particularities and appreciate the inventions of the human mind. However, symbolizations, that are basically cognitive in nature, may be contaminated by mistakenly attributing to them the status of value as such – even attributing higher meaning to symbolizations than to life itself -- by loading them with hierarchy and feelings of superiority over other groups. This constitutes, empirically and theoretically, conflation of symbolization and valuation. It leads to excessive particularism. Symbolizations are easily manipulated. Culturally 'manipulated,' people become highly aware of external differences and may develop a considerable degree of antagonism toward other groups. Symbolizations, that are cognitive in nature, are shareable in principle but need not be shared. The importance of values is more widely recognized. Neither individuals nor collectivities can do without making decisions about what is important in various situations. Most cultures treasure a positive evaluation of human relations, the family, devotion to work, respect for authority, love for nature, reverence of life itself as well as the simple pleasures of life. It is in the domain of values, which, as a whole, is much narrower than the domain of symbolizations, one can look for universalizing tendencies and a sense of unity of culture, even a world culture. But values cannot be imposed. To be useful to societies and individuals, values as ideas that are open to the future, need not be narrowly defined. The just mentioned values of work, of love for people and nature, reverence of authority etc., can be realized in various ways and need not lead to uniformity.However, values can be contaminated in two ways, firstly, by attributing excessive hierarchy to some values or trying to impose a set of values (NOTE: Aum), and secondly, by declaring that all values are of equal significance. Equalizing all values too would lead to excessive particularism and arbitrariness. Due to the property of complementariness and relative hierarchy, values cannot be equivalent. Paradoxically, a beneficial effect of becoming aware of common ground concerning values is that mutual differences may become more positive. Without that recognition, particularistic symbolizations tend to be divisive and oppressive even. With a common outlook on values and the ethical aspects of life, every culture and religion may be encouraged to maintain its own ritual community and symbolic universe. In recognizing a common humanity, these symbolic elements cease to be marks of difference and signs segregation, and the extent to which cultures and religions are diverse is considerably narrowed. This awareness and adopting related positions should make relations among religions and ethnic groups easier than at present is the case. Reimon Bachika, Professor, Dept. of Sociology, Bukkyo University, Kyoto, Japan

Note: This text is an abbreviation of a paper, under a slightly different title, that was presented at the XIXth Congress of the International Association of the History of Religions (IAHR), 24-30 March, 2005, Tokyo.

------------------------------------------- Tetrasociology and Values

by

Reimon Bachika, Japan, 2003

Read more: http://peacefromharmony.org/?cat=en_c&key=149

A New Theory of SocietyTetrasociology, formulated by Leo Semashko (2002), is a remarkable sociological theory. It is a multidimensional, critical theory of individual and social life. Semashko proposes a new model of society centering on its four basic resources: people, information, organization, and things/technology. In this respect, the theory is quite simple but it is rather complicated when it comes to societal coordination, which I will touch upon briefly in a moment. Tetrasociology is a theory with many political implications. It strives toward greater democratization. Its main political suggestion concerns a reformulation of the idea of stratified social classes based on property and social power into classes that are non-hierarchically ranked, based on the reproductive employment of people. In this sense, this theory is future-oriented. With an emphasis on values, it displays great moral concern for the well-being of all people everywhere. Further, it advocates the use of Esperanto as a common language to enhance world-wide multi-cultural communication. Beyond that, this theory recognizes the role of religion in society, and it advises religious leaders to unify their religious views in the manner of the Bahai religion, which offers a universalistic vision of all beliefs. Methodologically, this theory is both scientific and practical. It offers a relatively new statistical methodology based on quantifiable indices as well as a cultural technology for effecting social harmony. With all of this, Tetrasociology is a systemic, holistic theory that touches on all the important aspects of individual and social being. As such, it indeed is a remarkable sociological endeavor. Having only minimal knowledge of systems theory, I lack competence to review this work in that respect. So I will only comment on the perspective of values and belief, which have been central to my own study of the sociology of religion. But in order to discuss the value perspective, in this systems theory, I must touch briefly on its main features. Apparently, the main focus of tetrasociology is society. Semashko, so to speak, casts his net on society itself, "the social" in his words, to catch its main components and to describe their varying appearances and functioning. Deriving from the four resources, the basic social components of society are: human, informational, organizational, and material. Further, the reproductive structures of society are described as spheres. These are: the social sphere; the information sphere; the organizational sphere; and the technical sphere. It is these spheres that Semashko would like to see as the basis for rethinking social classes, grouping people in their main occupation either in humanitarian, informational, organizational, or technical employment. Remarkably again, Semashko conceives of individual human existence in a similar fashion, and reformulates the concept of the human personality accordingly. He sees individual persons as microcosms, constituted by variants of the same components as the social macrocosm. In people these components take the form of needs and abilities: human, informational, organizational, and material needs and abilities. Semashko then describes the four dimensions of personality as follows: character as the human component; consciousness as the informational component; will as the organizational component; and the body in all its relations as the material component. To repeat, people, information, organization, and things are the main social specimen that Semashko catches in his net. However, on opening the net, these specimen, as it were, spring forth in various transformations and categories of phenomena. The picture of society becomes complex. Resources are said to be static constants and their descriptions constitute "social statics." Societal structures are the structural constants and are treated as "social structuratics." Two other constants that Semashko elaborates are reproductive processes, described as "social dynamics," and states of development, as, "social genetics" - the latter two less important for present purposes. All four constants are said to be "coordinates" of society, which constitute "a four dimensional continuum" of social, human reality. It is the connections and relationships of the four constants and their various appearances that are the object of tetrasociological inquiry, which generates qualitative and quantitative descriptions. Tetrasociology and the Value PerspectiveLet us turn, now, to the value perspective in Semashko's work. I will begin with two pertinent quotes: "Ignorance of sphere classes [non-hierarchical social classes] … led in the past to total social disharmony in all its manifestations: class struggle, exploitation, wars, crime on a mass scale, terrorism, clash of civilizations, conflicts between religions, unfair distribution of wealth and power, a predatory attitude to[ward] nature, [in a word to] ‘one-dimensional man.’(H. Marcuse's term)" . . . "Total disharmony in the social world creates total disharmony in the traditional social actors: castes, estates, branch classes [hierarchically ranked social classes] . . . Sphere classes are new and harmonious social actors [that will realize] prosperity in the 21st century. (Semashko, 2002: 76, words in square brackets added). "The essence of a person’s humanitarian needs and abilities . . . consists in love [for] people, including self . . . Love is the pivot of personality, the backbone of the individual’s character . . . [Love] does not impoverish, but rather enriches each person both with regards to satisfaction of humanitarian needs and the development of humanitarian abilities . . . It is only in love that persons are not estranged (alienated) from each other . . . It is only [in] the state of love that [we find] ideal, harmonious, balanced relations between people; only the state of love ensures people’s true prosperity, true equality between them, freedom, fraternity, justice, humanness. Without love, the supreme feelings and values constituting the individual’s spirituality lose [their] authenticity and prove faulty and defective" (Semashko, 2002: 55, words in square brackets added). These quotes amply testify to the importance that Semashko attributes to values and harmony. He particularly stresses the importance of the latter. According to him, it is social harmony that, of all universal values, can save the world from self-destruction. According to him, social harmony is the oldest humanitarian value that already appeared in Homer's poems, that was understood by Aristotle as "the golden mean" and "the proportionality of the parts in a totality. Leibniz thought about "pre-established harmony." "The harmonious person" became an important idea of humanism. In Dostoevsky one finds expressions like "the beauty that will rescue the world." Semashko himself understands social harmony as the desire for and aspiration to balance between the spheres of society and between people, an ideal that may not be attainable, but efforts to achieve it are nevertheless deemed to be of paramount importance for humankind. Besides social harmony, Semashko discusses also the broader value system. He observes that industrial, bureaucratic society created a system of values including liberty, ownership of property, devotion to work, legal equality, personal advantage, independence, enlightenment, pluralism, pragmatism and democracy. He sees liberty and ownership of property as the pivotal pair of the system, and the value of liberty as the centre of its axis. on this basis, values such as justice, love, brotherhood, tolerance, non-violence, peace, humanism, equality of opportunities and the harmony of humankind were thought to develop. However, in the bureaucratic reality of the 19th and 20th centuries these values were overturned by injustice, hatred, enmity, intolerance, violence, war, lack of humanism, growing inequality and one-dimensionality. Semashko’s conclusion with respect to the value system is that bureaucratic organization, which was based on hierarchically ranked classes, was the main cause of social disharmony and negative values. If, in turn, societies could be organized based on sphere classes in accordance with the main employment of people as mentioned above, and if the political structure could be adapted following the same principle, social harmony would be greatly enhanced and positive values would follow in the wake of this social reorganization. Seen concretely, the four sphere classes would comprise people of different economic and social status but with similar expertise in various occupations and professions. Thus, not economic and social status but common employment in either the humanitarian, informational, organizational, or technical sphere would gradually create a new class consciousness. This reconstruction, according to Semashko, would eliminate class antagonism. Ideas, in common, of contributing to society would grow more and more in people’s consciousness, and lead to a more harmonious society, in place of benefiting from social organization through augmenting one’s power and wealth. It is in this sense that Semashko speaks of "the law of sphere harmony" that would replace "the law of disharmony" that naturally resulted from "the branch organization" of earlier, industrial society. Culture: Values and SymbolizationsThe question that I will now focus on is: How do values fit into Semashko’s systems theory? No doubt, moral concern, positive social values, and the ideal of social harmony are central emphases in Semashko’s thought. How are these morally noble thoughts integrated into Semashko’s sociological theory? That values are important to individuals is explained with respect to human character. Values are the humanitarian component of personality. The nature of values is not explained. As for social harmony, Semashko repeatedly mentions that it starts with harmony in the hearts of individuals (Semashko, 2002: 59, 88) but at the same time he stresses that people can develop good attitudes only when social harmony is being effected through "the sociocultural technology [engineering] of harmony," through the creation of "sphere democracy" (Semashko, 2002: 80-81). Thus, as is also indicated in Semashko’s conclusion with respect to the value system, values in effect are explicitly seen as tied to social structure and social organization. Social harmony will follow naturally when the right reorganization of society is put in place. Individuals and associations/organizations are not discussed as agents of social change. Evidently, the point of societal organizational is crucial. It is the organization of societies that determines who has the political power to implement social policies that, in turn, bear on people’s lives. Political power and economic power are major bones of contention, and not just in capitalistic societies. Material fortune or misfortune befalls those who can manipulate these goods or fail to do so. Also, to a great extent it is involvement in organizations that determines what the individual’s share will be. Semashko, therefore, is largely right in his insistence on the importance of the reorganization of social classes as central. A question that arises, here, concerns the degree of significance of societal organizations with respect to social change. Structural change is not the only type of social change. Change takes on many faces. It may occur in various areas of society, not just in the political arena. There are both rapid and slower occurrences of change in all four of Semashko’s spheres, depending on circumstances, historical conjunctions, the influence of specific social, political, and religious movements, new inventions in various fields, and eventually the propagation of new ideas and theories - including those of Semashko. Again, some events have great consequences, as for example, the student movement in the 1960s, the fall of the Berlin wall in 1989, and the nine/eleven terrorist attack on the USA in 2001. However it occurs, change seems to be a built-in phenomena of society and culture, but it is not one-directional. For all of this, sociocultural processes of change are hard to understand. As far as most social agencies are concerned, the concern is to know what types of social change are most desirable, and most effectively brought about at a particular historical junction. More importantly, there is our problem of values. I do not conceive of values as factors or variables in social life, nor as attitudes held by individuals that may result from social organization, as Semashko emphasizes. To me, values are cultural elements that must be discussed in a theory of culture that does not lose sight of human nature. A theory of culture, in my view, should be as important as a theory of society, because, as I argue below, culture is a reality sui generis, distinct from social reality. And recently we witnessed "a cultural turn" (Robertson, 1992), a considerable development of culture itself, in the study of culture, of which cultural studies is only one variety. In advanced societies there has been enormous outgrowths of popular culture, which is mainly expressive in quality. I have argued elsewhere that symbolizations and values constitute the core of culture (Bachika: 1999, 2000, 2002). The main point in my argument is that symbolizations and values are distinct core elements of culture, entailing distinct functioning, even though in reality these core elements are intertwined and therefore infrequently distinguished theoretically. Stated succinctly, symbolizations are cognitive devices, initially means of constructing new meaning. Seen theoretically they are modes of being and behavior. Values, in contrast, are ideas of being and behavior, that derive from behavior, and function as evaluations of meaning. In a pre-theoretical understanding it is clear that a value is very different from a symbol. When discussing culture, many authors focus either on symbols or on values. In order to see how they relate to one another, it is important to see differences as well as similarities (Bachika: 2001). Both are means of meaning construction, but in a very different way. To repeat, symbolizations are mainly cognitive in mode. Values, or valuations, while also cognitive, are mainly evaluative in mode. A short description of Buddhism and Christianity will clarify what I mean. Buddhism is the religion of the Law of all existence. The most important characteristics of the Law are interdependence of all existence (in Japanese mujo: non-constancy) and non-independence of human self (muga: no-self). These are complementary concepts. They imply that suffering is part of life, but also that liberation of suffering is possible. These are the four noble truths of Buddhism, which are symbolized by means of a wheel of a chariot. A wheel goes around and around and around. Ever the same rotation suggests, among other things, the unchangeable nature of the Law. (The idea of recurrence probably comes from the Indian view of reincarnation, a repetition of births). Christianity, on the other hand, has a very different system of symbolizations that probably developed out of very similar experiences within nature and reflections on the mystery of human existence, but developed within the worldview of Judaism. A primary element in the origin of the latter is the creation myth. A divine Being creates the first humans in its own image, but creation partly ends up in failure. The creatures rebel against their maker and sin becomes part of daily life, necessitating salvation. Christianity came to believe in Jesus as the redeemer, and the Cross became the core symbol of Christianity. Both Buddhism and Christianity are cognitive belief systems that nevertheless have very different symbol systems. The core problems they focus on are suffering and sin, respectively. Amazingly, these religions are very similar in what they value most. Their main moral commandments are the same: prohibition of killing, stealing, sexual promiscuity, and lying. The nature of morality in Christianity and Buddhism is different, that is, as a cognitive system, but the underlying valuation is much the same. Based on my view of culture, symbolizations and values - which I cannot explain here at any length - one can say that religious leaders need not unify their religious outlooks. on the contrary, it is culturally salutary that many different symbol/meaning systems enable people to marvel at the width and depth of the human mind. It is intellectually gratifying to continue to develop them. As diversity of biological species is a sign of the wonder of Life, so diversity of cultures, artefacts, scientific theories and so on are expressions of the wonder of the human mind. Let a thousand flowers bloom! on the other hand, it seems both easier and more useful for religious leaders to unify their moral outlooks and to rally behind common values that are already out there. The human heart is not as diverse and complicated as the human mind. A thousand flowers come only in a variety of blue, yellow, and red, the three main colors. Why would a declaration of common core values be useful for the future of societies? Defined as ideas about being and behavior, values are, as Semashko implies in his view of harmony, a matter of inspiration and enlightenment. These attitudes cannot be imposed. Values, social or spiritual, profane or religious, should not be seen as commandments or norms. Religious communities should be, of all things, spiritual and moral communities, inspiring people toward happy and peaceful lives. If religious bodies would get behind one set of core values, compatible with secular formulations, both religious and secular thought would become more plausible and respected. A theoretical implication of this view is that values are not necessarily tied to any specific symbol/meaning system, nor to any form of social organization. Values belong to a distinct "sphere" of human reality: culture. Within social reality they represent its specific tone: morality. I maintain, in a similar fashion as Semashko, that morality and ideals of living must be upheld by society, but also by individual associations and organizations. It is these which should be the most rational existences in society. Certainly, there are many exceptionally virtuous individuals, but, judging from individual human nature, humans are naturally selfish, wishy-washy in their mind sets, and from birth, on, in need of mental orientation. And yet, however dependent one is on society and fellow humans, to live meaningfully one needs a sense of autonomy. Toward a New Enlightenment Semashko dreams of a new enlightenment and a new world order. Interestingly, these ideas seems to have reached a measure of maturity during his Marxist education, in the heydays of the Soviet Empire, although probably in the ‘Marxian white nights’ at St. Petersburg! I mean, influence from Marx seems considerable. Semashko critically focuses on the Unterbau of society and class structure. He criticizes the value of liberty that he sees as the focal point of the axis of the value system from which, like a Pandora box, many evils have escaped into society. He wants to improve on equality - without absolutizing this value - between the various classes, men and women, the younger and the older generation, giving voting rights to children. He even envisions a new, non-violent revolution to be realized through "a sociocultural technology [engineering] of harmony." One particular image in Semashko’s vision seems to be blurred, the image of culture. He appears to have conceptually neglected culture. Though much concerned with the cultural content in the "informational sphere" and "human character," culture as a term is not part of Semashko’s conceptual scheme. Society is philosophically defined as "social space-time." I would add the dimension of culture to this core concept (making it four dimensional, too). No doubt, the study of culture was not central to Marx, and in a certain sense, neither to the other classical sociologists like Durkheim, Weber, and Parsons. The relations between individual and society, social solidarity, collective consciousness, rationality, social stability and the like were their central concepts. None of them developed a new theory of culture (Martindale, 1971; Guy, 1974). Present societies are less saddled with social than with cultural problems: family life, personal human relations, diversified life styles, an overdose of materialistic and hedonistic values, the new ‘dogma’ of postmodern uncertainty, the moral problems of biochemical/biological engineering, and so on. Transforming or improving societies is no sinecure. Among the many things one needs to be concerned about, attention to power relations and value systems is, no doubt, most crucial. But the enlightenment that present-day societies and people are most in need of is enlightenment of the human heart. References: Bachika, Reimon. (1999). "Differentiation of Culture and Religion," Bukkyo daigaky shakaigakubu ronso. 32: 47-64. _____. (2000). "Values and Sociocultural Change" Paper presented at the Research Council Conference of the International Sociological Association, University of Montreal, Canada. _____. (2001). "Adoption of Universal Values: Creating an Ethos for community for the 21st Century" Paper presented at the International Conference organized by Research Committee 07 of the ISA (Futures Research) and the Palas Athena Institute, Sao Paulo, Brazil, September 17-19, 2001. _____. (2002). Religion as a Fundamental Category of Culture. Traditional Religion and Culture in a New Era. Reimon Bachika Editor. Transaction Publishers, New Brunswick (USA) and London (UK): 193-220. Martingdale, D. (1971). "Max Weber on the Sociology and Theory of Civilization" in P.Hamilton (ed.) Max Weber: Critical Assessments, II. Routledge. Robertson, Roland. (1992). Globalization: Social Theory and Global Culture. London: Sage Rocher, Guy. (1974). Talcott Parsons and American Sociology, Nelson. Semashko, Leo. (2002). Tetrasociology: Responses to Challenges. Technical University, Russia, St. Petersburg. Reimon Bachika, Professor, Dept of sociology, Bukkyo University, Kyoto, Japan. President ISA RC 07 Futures Research, International Sociological Association ---------------------------

Up

|