| |

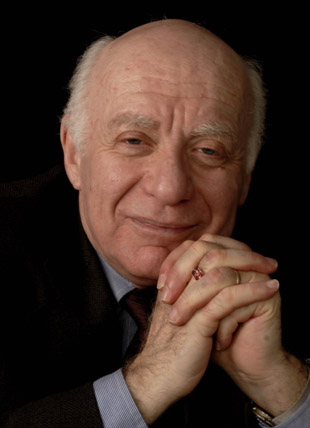

Michael Brenner, Ph.D.

Michael Brenner is Professor Emeritus of International Affairs at the University of Pittsburgh and a Fellow of the Center for Transatlantic Relations at SAIS/Johns Hopkins.

See his personal page:

https://peacefromharmony.org/?cat=en_c&key=775 Putin on The Role Of The State In The Economy Most of the commentators on yesterday's post were right. It was the Russian President Vladimir Putin who said this: | Many of us read The Little Prince by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry when we were children and remember what the main character said: “It’s a question of discipline. When you’ve finished washing and dressing each morning, you must tend your planet. … It’s very tedious work, but very easy.” I am sure that we must keep doing this “tedious work” if we want to preserve our common home for future generations. We must tend our planet. The subject of environmental protection has long become a fixture on the global agenda. But I would address it more broadly to discuss also an important task of abandoning the practice of unrestrained and unlimited consumption – overconsumption – in favour of judicious and reasonable sufficiency, when you do not live just for today but also think about tomorrow. We often say that nature is extremely vulnerable to human activity. Especially when the use of natural resources is growing to a global dimension. However, humanity is not safe from natural disasters, many of which are the result of anthropogenic interference. By the way, some scientists believe that the recent outbreaks of dangerous diseases are a response to this interference. This is why it is so important to develop harmonious relations between Man and Nature. |

It was a part of a talk he gave at this year's Valdai Discussion Club meeting. I found the excerpt remarkable because it included this, on might say, anti-capitalistic statement: | .. an important task of abandoning the practice of unrestrained and unlimited consumption – overconsumption – in favour of judicious and reasonable sufficiency, when you do not live just for today but also think about tomorrow. |

That 'green' statement will rile those people who argue for free markets and a right to sell bullshit in ever more flavors. In their view the fight against such 'communists' thinking must be renewed. As the full English transcript of Putin's speech and the two and a half hour Q&A is now available I can also quote another interesting passage where Putin talks about capitalism and the role of the state. His standpoint seems very pragmatic to me: | Question: Mr President, there has been much talk and debate, in the context of the global economic upheavals, about the fact that the liberal market economy has ceased to be a reliable tool for the survival of states, their preservation, and for their people. |

| Pope Francis said recently that capitalism has run its course. Russia has been living under capitalism for 30 years. Is it time to search for an alternative? Is there an alternative? Could it be the revival of the left-wing idea or something radically new? Putin: Lenin spoke about the birthmarks of capitalism, and so on. It cannot be said that we have lived these past 30 years in a full-fledged market economy. In fact, we are only gradually building it, and its institutions. [..] You know, capitalism, the way you have described it, existed in a more or less pure form at the beginning of the previous century. But everything changed after what happened in the global economy and in the United States in the 1920s and 1930s, after World War I. We have already discussed this on a number of occasions. I do not remember if I have mentioned this at Valdai Club meetings, but experts who know this subject better than I do and with whom I regularly communicate, they are saying obvious and well-known things. When everything is fine, and the macro economic indicators are stable, various funds are building up their assets, consumption is on the rise and so on. In such times, you hear more and more that the state only stands in the way, and that a pure market economy would be more effective. But as soon as crises and challenges arise, everyone turns to the state, calling for the reinforcement of its supervisory functions. This goes on and on, like a sinusoidal curve. This is what happened during the preceding crises, including the recent ones, like in 2008. I remember very well how the key shareholders of Russia’s largest corporations that are also major European and global players came to me proposing that the state buy their assets for one dollar or one ruble. They were afraid of assuming responsibility for their employees, pressured by margin calls, and the like. This time, our businesses have acted differently. No one is seeking to evade responsibility. on the contrary, they are even using their own funds, and are quite generous in doing so. The responses may differ, but overall, businesses have been really committed to social responsibility, for which I am grateful to these people, and I want them to know this. Therefore, at present, we cannot really find a fully planned economy, can we? Take China. Is it a purely planned economy? No. And there is not a single purely market economy either. Nevertheless, the government’s regulatory functions are certainly important. [..] We just need to determine for ourselves the reasonable level of the state's involvement in the economy; how quickly that involvement needs to be reduced, if at all, and where exactly. I often hear that Russia’s economy is overregulated. But during crises like this current pandemic, when we are forced to restrict business activity, and cargo traffic shrinks, and not only cargo traffic, but passenger traffic as well, we have to ask ourselves – what do we do with aviation now that passengers avoid flying or fly rarely, what do we do? Well, the state is a necessary fixture, there is no way they could do without state support. So, again, no model is pure or rigid, neither the market economy nor the command economy today, but we simply have to determine the level of the state's involvement in the economy. What do we use as a baseline for this decision? Expediency. We need to avoid using any templates, and so far, we have successfully avoided that. |

Then comes a paragraph that shows where Russia differs from the current 'western' economic policies of negative interest rates and deflation: | Of course, the Central Bank and the Government are among the most important state institutions. Therefore, it was in fact through the joint efforts of the Central Bank and the Government that inflation was reduced to 4 percent, because the Government invests substantial resources through its social programmes and national projects and has an impact on our monetary policy. It went down to 3.9 percent, and the Governor of the Central Bank has told me that we will most likely keep it around the estimated target of around 4 percent. This is the regulating function of the state; there is no way around it. However, stifling development through an excessive presence of the state in the economy or through excessive regulation would be fatal as well. You know, this is a form of art, which the Government has been applying skilfully, at least for now. |

Keeping inflation up by a bit will make it easier for Russian consumers and companies to pay back their loans. It is economically healthier than the deflationary policies of western societies. Russia is well on its way to overtake Germany as the fifth biggest economy. Putin's pragmatic positions towards the role of the state in the economy and his relative generous policies of social programs and large national projects have contributed to that. The many questions and answers on foreign policy in the Valdai talk show a similar pragmatism on other issues. For those interested in those here is again the link to the transcript. Posted on October 24, 2020 at 18:00 UTC | Permalink Friends & Colleagues (01-11-20), I have received an uncommon number of replies to the material re. Vladimir Putin which I distributed a few days ago. That is not entirely surprising. People find it hard to make him out. He gets under their skin. Unusually, that seems due less to what the man actually does than what he is. I personally have a far more benign view of Putin as a statesman than most others. That has come across in other commentaries of mine. To delve into detail, though, is not the point of these remarks. I simply will make two assertions. one, he has been more forthright in elaborating his views about world affairs, his conception of Russia's place in the world system, and the most salient issues of his times than any other leader of a major power whom I can recall. Two, the vast majority of the analysis and interpretation of Putin and his policies is singularly distorted, misleading and often a downright misrepresentation.1

The question that fascinates me is "why is this?" In trying to answer it, I will climb farther out on the limb where I already am perched. The first thing to say is that it is normal for humans to be anxious, if not fearful, of what they don't understand. Putin is not easily understood because he fits into no simple category. He is not a 'type.' His complex personality demands an unusual amount of application and sophistication. Both qualities are scant these days.

Second, he stands in stark contrast to his predecessor - and, perhaps more important, what we expected of a post-Soviet Russian chief. Stephen F. Cohen put it succinctly:

“At the time of Putin’s succession, they expected and wanted a sober Yeltsin. That is to say someone content to be subservient to the United States, marginalized in Europe and a non-factor elsewhere in the world. In addition, lucrative investment opportunities were foreseen in the usual neo-liberal fashion. It soon became apparent, though, that Putin was a formidable leader bent on applying his singular talents to restoring the Russian state and the country’s legitimate place in global affairs. That made him, and the renewed Russia that he was fashioning, unpalatable.”

That turn of events greatly irritates us. For it complicates American foreign policy, it challenges our vision of a liberal "new world order," and it implicitly raises uncomfortable doubts as to whether our America-centered conception of world history as a pageant of progress is as immutable as we have thought.

A third element is that of envy. At the top, where ambition is rampant, envy accompanies it. Putin is difficult to match. Our leaders experience him as an intellectually, ideologically and in his cool-headed political mastery as well – a rare commodity. Obama couldn't stand the man. That was not because Putin's Russia did anything outrageous to threaten the United States. Rather, it stemmed from the psychology of a somebody who himself exhibits a pronounced superiority complex and who then encounters someone as intelligent as he, at least as well read, better versed in the ins-and-outs of international affairs and possessing far more sophisticated diplomatic skills. Moreover, Putin has the well thought-out convictions which is Obama’s short suit. Perhaps most disconcerting, Putin has the habit of meaning what he says and then doing it. one might assume that such a trait would appeal to his interlocutor. Instead, in the minds of Western leaders that just makes him all the odder, since they themselves habitually pursue fragmented policies unguided by coherent design or sustained strategy.* (Besides: what do you make of a grave Kremlin leader who records a quite passable version of Blueberry Hill in English. Imagine the stir in Moscow if Obama responded with Moscow Nights in Russian!)

Finally, truly exceptional persons who know what they're about and have the rare quality of being prepared to act on it in other than a narrow instrumental fashion trouble us. They are unpredictable. They might do things we are unprepared for. Their motives might not be as narrowly self-interested as we are accustomed to. Logically, the most fruitful way to deal with them is through candid engagement. Putin's combination of self-confidence, clarity of thought and articulateness open the way to doing exactly that. Is there anyone on our side ready and able to do so?

P.S. China’s Xia poses a somewhat similar dilemma, although the West’s mode of address has been more modulated. Apprehensions about China are more deep-seated and Xi is a less accessible personage.

Pelosi’s irrational, petulant reaction to Alexandra Octavio-Cortes Michael Brenner mbren@pitt.edu 01-11-20 ------------------------------ Я получил необычное количество ответов на материал о Владимире Путину, который я послал несколько дней назад. Это совсем не удивительно. Людям трудно его разглядеть. Он попадает под их кожу. Необычно то, что это, кажется, связано не столько с тем, что мужчина на самом деле делает, сколько с тем, чем он является. Лично я отношусь к Путину как к государственному деятелю гораздо более благосклонно, чем большинство других. Это встречалось в других моих комментариях. Однако в этих замечаниях не стоит вдаваться в подробности. Я просто сделаю два утверждения. Во-первых, он был более откровенен в изложении своих взглядов на мировые дела, своей концепции места России в мировой системе и наиболее важных вопросов своего времени, чем любой другой лидер крупной державы, которого я могу припомнить. Во-вторых, подавляющее большинство анализа и интерпретации Путина и его политики исключительно искажены, вводят в заблуждение и часто являются откровенным искажением.

Меня очаровывает вопрос: «Почему это?» Пытаясь ответить на него, я вылезу дальше по той ветке, где я уже сидел. Первое, что нужно сказать, это то, что для людей нормально беспокоиться, если не бояться того, чего они не понимают. Путина нелегко понять, потому что он не попадает в простую категорию. Он не типаж. Его сложная личность требует необычайной сложности и изысканности. В наши дни оба качества скудны.

Во-вторых, он резко контрастирует со своим предшественником - и, что, возможно, более важно, тем, чего мы ожидали от постсоветского российского вождя. Стивен Коэн лаконично выразился:

«Во время преемственности Путина они ожидали и хотели трезвого Ельцина. То есть кто-то довольствуется тем, что подчиняется Соединенным Штатам, маргинализирован в Европе и не играет роли где-либо еще в мире. Кроме того, в обычной неолиберальной манере были предусмотрены прибыльные инвестиционные возможности. Однако вскоре стало очевидно, что Путин был грозным лидером, стремящимся применить свои уникальные таланты для восстановления российского государства и законного места страны в мировых делах. Это сделало его и обновленную Россию, которую он создавал, неприятными ».

Такой поворот событий нас очень раздражает. Потому что это усложняет американскую внешнюю политику, бросает вызов нашему видению либерального «нового мирового порядка» и косвенно порождает неприятные сомнения в том, является ли наша ориентированная на Америку концепция мировой истории как зрелища прогресса столь же неизменной, как мы думали. Третий элемент - это зависть. Наверху, где безудержно амбиции, им сопутствует зависть. Путину сложно сравниться. Наши лидеры воспринимают его как интеллектуально, идеологически и в его хладнокровном политическом мастерстве - редкость. Обама терпеть не мог этого человека. Это произошло не потому, что путинская Россия сделала что-то возмутительное, чтобы угрожать Соединенным Штатам. Скорее, это проистекает из психологии человека, который сам демонстрирует ярко выраженный комплекс превосходства, а затем встречает кого-то столь же умного, как он, по крайней мере, так же начитанного, лучше разбирающегося во всех тонкостях международных отношений и обладающего гораздо более искушенными. дипломатические навыки. Более того, у Путина есть хорошо продуманные убеждения, каковым является короткий костюм Обамы. Пожалуй, больше всего сбивает с толку то, что Путин имеет привычку иметь в виду то, что он говорит, а затем делать это. Можно было предположить, что такая черта понравится его собеседнику. Напротив, в сознании западных лидеров это делает его еще более странным, поскольку они сами обычно проводят разрозненную политику, не руководствуясь последовательным планом или устойчивой стратегией. * (Кроме того: что вы думаете о серьезном кремлевском лидере, который записывает вполне сносную версию BlueberryHill на английском языке. Представьте себе переполох в Москве, если бы Обама ответил московскими вечерами на русском языке!) Наконец, нас беспокоят поистине исключительные люди, которые знают, что они собой представляют и обладают редким качеством готовности действовать в соответствии с этим иначе, чем узко инструментальным способом. Они непредсказуемы. Они могут делать то, к чему мы не готовы. Их мотивы могут быть не столь эгоистичны, как мы привыкли. Логично, что самый плодотворный способ справиться с ними - откровенное общение. Комбинация Путина уверенности в себе, ясности мысли и ясности формулировок открывает путь именно к этому. Есть ли кто-нибудь на нашей стороне, готовый и способный это сделать?

P.S. Си в Китае ставит во многом аналогичную дилемму, хотя способ обращения Запада был более модулированным. Опасения по поводу Китая более глубоки, а Си - менее доступный персонаж.

° На более домашнем уровне можно увидеть грубую аналогию в иррациональной, раздражительной реакции Нэнси Пелоси на Александру Октавио-Кортес Майкл Бреннер mbren@pitt.edu 01-11-20 --------------------------------

Up

|